Biomass reactor studied for removing combustor CO2

An Ohio University team has proposed growing and harvesting the organisms directly in the exhaust gas from power plants, thereby absorbing the CO2 from the plant's emissions.

Moreover the algae grown could be collected from the power plants for use by agricultural industries, says David Bayless, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at OU and lead researcher of the project.

"Once the algae is grown, if it can't be used as fuel or a hydrogen source, it can be used as a fertilizer or soil stabilizer," said Bayless, who also serves as associate director of the university's Ohio Coal Research Center.

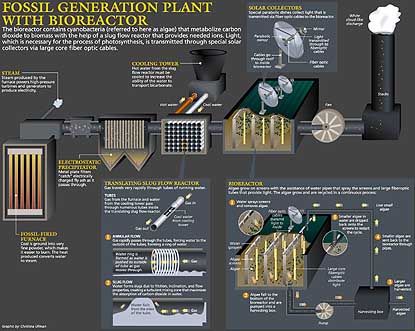

The process, he said, is designed to work something as follows:

As the carbon dioxide exhaust moves toward the smokestacks, it would pass through tubes of running water, creating bicarbonates. The water then would flow through a bioreactor* that contains a series of screens on which algae grow. "The algae basically drink the bicarbonates," said Bayless, "They get carbon through this system much quicker than trying to get it out of the air."

Using a system of solar panels, satellite dishes, and fiber-optic cables developed by scientists at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, a partner in the project, only visible sunlight would be emitted into the bioreactor, helping the algae use the carbon dioxide for fuel during photosynthesis.

Once the algae grow to maturity, they fall to the bottom of the bioreactor and for harvesting and other uses, says Bayless, who is collaborating on the project with Morgan Vis-Chiasson and Gregory Kremer. The former is an assistant professor of environmental and plant biology who specializes in algae research; the latter is an assistant professor of mechanical engineering; both are at Ohio University.

Until now, the Ohio University team has tested the method on a small scale, growing about 2 lbs of algae in a direct stream of carbon dioxide exhaust with the aid of fluorescent lights.

Hereafter, the team will use a three-year U.S. Department of Energy grant to will allow them to add the bicarbonate-producing and sunlight systems to the project.

Researchers will use blue-green algae—collected from Yellowstone National Park by Montana State University colleagues—that survive near-boiling-point temperatures in hot springs—conditions that should serve them for their use at a coal-fired power plant.

The researchers' ultimate goal is to create technology that can use any type of alga.

Bayless estimates that, using this technology, an average-size plant could process 20% of its carbon dioxide emissions and produce 200,000 tons or more of algae per year.

No single technology can solve the carbon dioxide problem for coal-burning power plants, Bayless stresses, but the algae-fueled bioreactor could serve as an efficient, cost-effective part of the gas-emission reduction strategy.

Bayless and Kremer hold appointments in the Russ College of Engineering and Technology. Vis-Chiasson holds an appointment in the College of Arts and Science.

Contact: College of Arts & Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH, 45701. Tel: 740-593-2845

*The bioreactor is one of several energy technologies being developed by Bayless and other scientists with the university's Ohio Coal Research Center to make Ohio coal a cleaner, more viable fuel source. In other projects supported by the Ohio Coal Development Office, the researchers are exploring ways to reduce toxic sulfur emissions and are developing a new device that to more efficiently collect heavy-metal particles from the exhaust stream.

The previous case study was adapted from a release written by Andrea Gibson who works for Ohio University.